Somali killings reveal ugly side of elite regiment

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:01PM

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:01PM

By David South

Now Magazine (Toronto, Canada), May 6-12, 1993

Canada is touted around the world for its commitment to the ideals of peacekeeping. But something went seriously wrong with the Canadian Airborne Regiment at Belet Huen in Somalia.

Since the revelation of the March 16 shooting death of Somali civilian Shidane Omar Aroni at the hands of members of the regiment, three more killings of civilians by Canadian troops have come to light. Two of the deaths, including Aroni’s, are being investigated internally by the military, while others are subject to a government-ordered inquiry.

Military watchers say the problem permeating the Canadian Armed Forces' approach to peacekeeping goes beyond the inappropriate behaviour of a few gung-ho members of the airborne.

Warning ignored

They say the department of national defence has ignored the warnings of the United Nations and its own internal papers regarding the ever more complex duties of international peacemaking and peacekeeping. The Canadian forces and other coalition partners, they say, are playing with fire in Somalia by neglecting to prepare troops with the skills they need in negotiation, conflict resolution and cultural sensitivity.

And they point out that the assigning of peacekeeping duties to the Canadian airborne – an elite force with a fearsome reputation – illuminates everything that is wrong with the current approach.

“The opposition is calling for the airborne to be dismantled, but they are prepared for high-intensity combat,” says defence consultant Peter Langille. “It’s just a dumb decision – somebody used them for the wrong thing.”

If Canadian personnel were properly trained, the incidents at Belet Huen would not have happened, says Gideon Forman of the Canadian Peace Alliance.

“Peacekeeping is a special skill that requires courses in non-violent conflict resolution and negotiation. A peacekeeping training centre – which the Canadian Forces pooh-pooh – would be very useful.”

Indeed, the unfolding of the horrifying drama in Belet Huen posed acutely difficult problems for army personnel. It took a small-town journalist on a press junket intended to show off the work of the airborne to force the army to go public with the death of Aroni.

Jim Day of the Pembroke Observer, located near the airborne’s home base at CFB Petawawa, spotted a commotion over the attempted suicide of master corporal Clayton Matchee, one of the soldiers arrested in the death.

It wasn’t until March 31, two weeks after an internal military investigation had begun, that the military admitted to the investigation.

Day says watching the troops in Somalia made it clear there was a mismatch between the personnel and the mission.

“They are trained for a combative role. They’re considered the cream of the crop, very tough physically. They want to use their training, as opposed to being trained for combat in rugged exercises and then ending up handing out water.

“What hit me quite strongly down in the camp was how they spent their leisure time. I watched them set up a spider fight. They had such intensity – they were watching these two spiders devour each other for 20 or 25 minutes, coaching them along, pumping their arms in the air and rooting and screaming.”

Creates aggression

Observers who know the regiment say the training is meant to create extremely aggressive behaviour while reinforcing elite status. Through “jump school” – three weeks of punishing training where subjects drop from planes – soldiers experience exhilarating highs and terrifying lows.

Anecdotes abound about the secretive and violent behaviour of the regiment.

“There’s a good deal of resentment,” says Dave Henderson, who puts together a weekly news infomercial called Base Petawawa Journal for Ottawa’s CHRO TV. “A lot of the other soldiers on the base shun them. Their nickname in some quarters is ‘stillborne.’

“I know from people in other military outfits that when you go up against the airborne, there is a fear factor,” says Langille, whose company Common Security Consultants, has lobbied the government to change peacekeeping training.

“In exercises where the airborne take over a base or something, if they catch you, they beat the shit out of you. It’s not surprising they got carried away in an ugly environment.”

Frustrating pace

Nor is it strange that the regiment chafed at the pace of the Somalian daily round. “The soldiers believe the Somalis are very slow in their ways,” says Day. “They’re used to ‘boom, boom.’ Whatever it is they do, even if it’s building a trench or putting up a fence, they are very quick about it.”

But the military argues that the best preparation for peacemaking and peacekeeping duties is the general combat training every soldier receives.

“The best peacekeeper is a well-trained soldier,” says veteran peacekeeper colonel Sean Henry of the Conference of Defence Associations.

“When you look at the make-up of the coalition force in Somalia, you find that just about every other nation has contributed either airborne troops or special troops, simply because they wanted a well-trained unit at short notice.”

Henry thinks those who argue for peacekeeping training are missing the essence of the armed forces mandate. “It’s counter-productive. You might as well forget about the armed forces and sign up a bunch of social workers.”

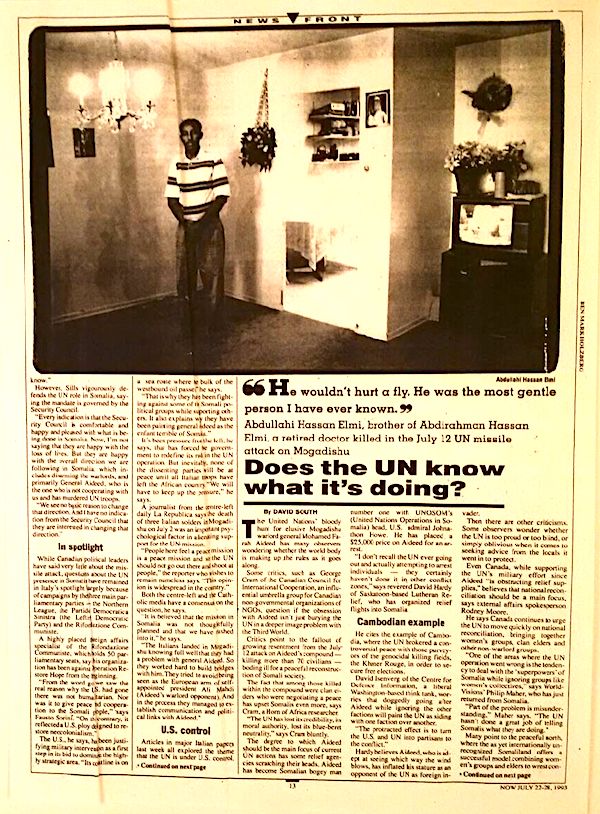

Does the UN know what it’s doing?

By David South

Now Magazine (Toronto, Canada), July 22-28, 1993

The United Nations’ bloody hunt for elusive Mogadishu warlord general Mohamed Farah Aideed has many observers wondering whether the world body is making up the rules as it goes along.

Some critics, such as George Cram of the Canadian Council for International Cooperation, an influential umbrella group for Canadian non-governmental organizations of NGOs, question if the obsession with Aideed isn’t just burying the UN in a deeper image problem with the Third World.

Critics point to the fallout of growing resentment from the July 12 attack on Aideed’s compound – killing more than 70 civilians – boding ill for a peaceful reconstruction of Somali society.

The fact that among those killed within the compound were clan elders who were negotiating a peace has upset Somalis even more, says Cram, a Horn of Africa researcher.

“The UN has lost its credibility, its moral authority, lost its blue-beret neutrality,” says Cram bluntly.

The degree to which Aideed should be the main focus of current UN actions has some relief agencies scratching their heads. Aideed has become Somalian bogey man number one with UNOSOM’s (United Nations Operations in Somalia) head, US Admiral Johnathon Howe. He has placed a $25,000 price on Aideed for an arrest.

“I don’t recall the UN ever going out and actually attempting to arrest individuals – they certainly haven’t done it in other conflict zones,” says reverend David Hardy of Saskatoon-based Lutheran Relief, who has organized relief flights into Somalia.

Cambodian example

He cites the example of Cambodia, where the UN brokered a controversial peace with those purveyors of the genocidal killing fields, the Khmer Rouge, in order to secure free elections.

David Isenverg of the Center for Defense Information, a liberal Washington-based think tank, worries that doggedly going after Aideed while ignoring the other factions will paint the UN as siding with one faction over another.

“The protracted effect is to turn the US and UN into partisans to the conflict.”

Hardy believes Aideed, who is adept at seeing which way the wind blows, has inflated his stature as an opponent of the UN as foreign invader.

Then there are other criticisms. Some observers wonder whether the UN is too proud or too blind, or simply oblivious when it comes to seeking advice from the locals it went in to protect.

Even Canada, while supporting the UN’s military effort since Aideed “is obstructing relief supplies,” believes that national reconciliation should be a main focus, says external affairs spokesperson Rodney Moore.

He says Canada continues to urge the UN to move quickly on national reconciliation, bringing together women’s groups, clan elders and other non-warlord groups.

“One of the areas where the UN operation went wrong is the tendency to deal with the ‘superpowers’ of Somalia while ignoring groups like women’s collectives,” says World Visions’ Philip Maher, who has just returned from Somalia.

“Part of the problem is misunderstanding,” Maher says. “The UN hasn’t done a great job of telling Somalis what they are doing.”

Many point to the peaceful north, where the as yet internationally unrecognized Somaliland offers a successful model, combining women’s groups and elders to wrest control.

"Does the UN know what it's doing?": Now Magazine, July 1993.

"Does the UN know what it's doing?": Now Magazine, July 1993.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

1993,

1993,  Canada,

Canada,  David South,

David South,  Now Magazine,

Now Magazine,  Somalia,

Somalia,  Toronto,

Toronto,  airborne,

airborne,  investigative journalism,

investigative journalism,  killings,

killings,  national defence,

national defence,  peacekeeping,

peacekeeping,  regiment in

regiment in  Africa,

Africa,  Canada,

Canada,  David South Consulting,

David South Consulting,  Magazine Stories 1990s,

Magazine Stories 1990s,  Media,

Media,  Now Magazine,

Now Magazine,  Peacekeeping,

Peacekeeping,  Poor,

Poor,  Somalia,

Somalia,  Toronto,

Toronto,  United Nations,

United Nations,  United Nations Mission,

United Nations Mission,  Women,

Women,  Youth

Youth