New student group seeks 30 percent tuition hike

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:18PM

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:18PM

Coalition hoping to be the “responsible” campus alternative

By David South

Now Magazine (Toronto, Canada), December 17-23, 1992

While the provincial government’s decision to eliminate most student grants has many students worrying about meeting the increasing costs of higher education, a new student group is lobbying the province to hike tuition.

The Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance (OUSA) is a coalition of executives from student councils at the University of Toronto – the biggest in Canada – as well as Queen’s, Brock, the University of Waterloo and Wilfred Laurier.

Those councils used to be members of the Ontario Federation of Students (OFS), the province’s major student organization, representing more than 200,000 students at 31 colleges and universities.

But there have been disagreements within the OFS over its policy that tuition fees be abolished. The five dissident student councils got together last month and launched OUSA to address what they say is “the worst underfunding crisis in recent memory.”

The group calls for a 30-per-cent increase in tuition over the next three years, an about-face from the stance of most mainstream student organizations, which call for, at the very least, a tuition freeze. Both the OFS and the Canadian Federation of Students have a zero-tuition policy.

“Until now, student groups have been whining, but our approach is reasonable,” says Farrah Jinha, president of U of T’s Students’ Administrative Council, which left OFS a decade ago. “OUSA is setting a limit on how much tuition can increase and with very specific conditions.”

OUSA’s plan calls for the provincial government to match, dollar-for-dollar, any increase in student fees. In conjunction with a 5-per-cent increase in private sector contributions, this would infuse an expected $360 million into higher education, says OUSA.

Political lobbyist Titch Dharamsi – a former vice-president of SAC and high-profile organizer for the Liberal party – has carried over his lobbying duties to OUSA.

Gimme gimme

Dharamsi says OUSA isn’t out to rival OFA and is just being “realistic.” “The public likes our ideas. They are real, workable solutions. We recognize the province’s fiscal problems. It’s not just ‘gimme, gimme’ anymore.”

Jinha says the policy positions of the OFS don’t have much in common with everyday student concerns.

“People felt it wasn’t worth the money,” she says. “Many students across the province were frustrated with OFS taking stands on non-student issues like abortion, decriminalizing marijuana or the Gulf war. We wanted a group which would focus more on issues like teaching quality and accessibility to funding.”

OUSA claims to represent 85,000 students. Staff have been hired and equipment purchased for the group’s unmarked office in the suites of a University Avenue law firm. “We are in this for the long haul,” Dharamsi says.

OUSA has caught the eye of colleges and universities minister Richard Allen, whose party shares a zero-tuition policy with the OFS. But now that the NDP finds itself governing during a recession, Allen’s views sound more like OUSA’s.

“The party policy on tuition is symbolic,” he says. “It says we want to address barriers to post-secondary education.”

Student quits

One student representative on U of T’s Students’ Administrative Council, Jason Zeidenberg, resigned when SAC decided to join OUSA.

“The process hasn’t involved students,” says Zeidenberg. “It is a policy for student politicians, not students. OUSA has no constitution, no financial structure, no mechanism for individual students to bring questions forward. It is an undemocratic, fly-by-night institution.

“Until they justify their expenditures, they are under suspicion of being a front group to legitimize policies like raising tuition.”

OUSA isn’t legally obliged to incorporate itself or provide a constitution or accountable executive. The group operates much like a club, with member council executives making decisions collectively, and funds coming out of member unions’ budgets.

Joining OFS requires a student referendum, but because of OUSA’s quasi-ad-hoc status, no such vote is needed to join the new group.

Dharamsi says this approach is cost-effective and flexible. He says OUSA has spent around $10,000 to date, but can’t offer a fixed budget.

Zeidenberg hs organized several college and faculty student unions at U of T to demand that SAC hold a referendum about membership in OUSA.

Craft doesn’t feel that OUSA is a threat. “I’m not losing sleep over it,” he says. “We’re considered the representatives of students in Ontario.”

Recently, however, the University of Western Ontario pulled out of OFS and is currently negotiating with OUSA about joining. Western’s departure takes another 20,000 students and precious dollars with them, and funding cuts have led OFS to lay off staff.

Read the original story here: New student group seeks 30 percent tuition hike

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

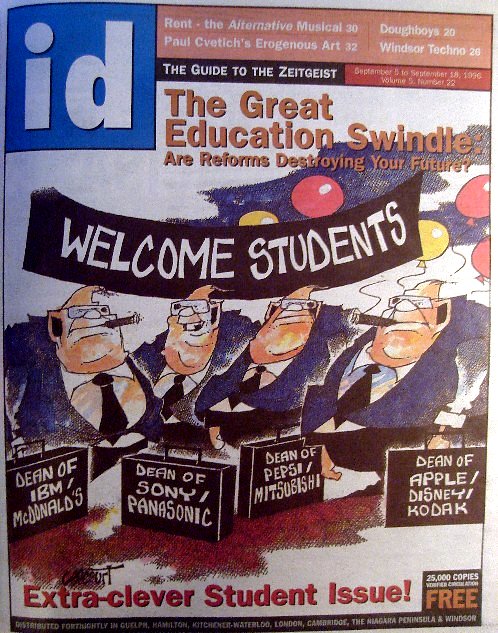

This cover is by great Canadian political cartoonist and illustrator Jack Lefcourt. Always funny, Jack captures well the corporate take-over of the country’s universities and the introduction of the catastrophic debt culture that leaves so many students in a financial pickle. It was also Id’s first student issue. Id Magazine: Student Issue, “The guide to the zeitgeist”, Ontario, 1996, Features Editor: David South.

This cover is by great Canadian political cartoonist and illustrator Jack Lefcourt. Always funny, Jack captures well the corporate take-over of the country’s universities and the introduction of the catastrophic debt culture that leaves so many students in a financial pickle. It was also Id’s first student issue. Id Magazine: Student Issue, “The guide to the zeitgeist”, Ontario, 1996, Features Editor: David South.

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2021