By David South

Id Magazine (Canada), July 11-25, 1996

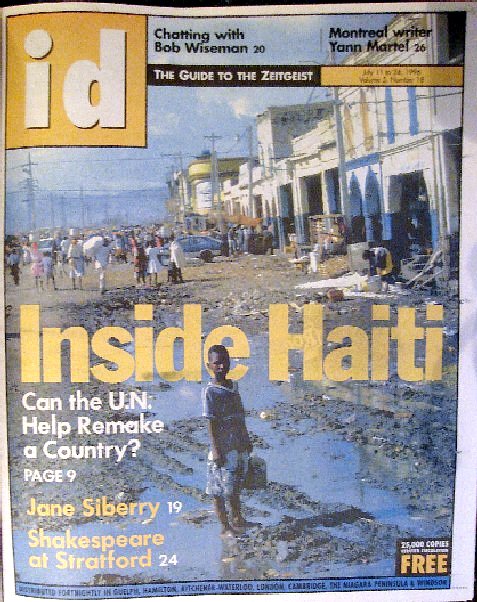

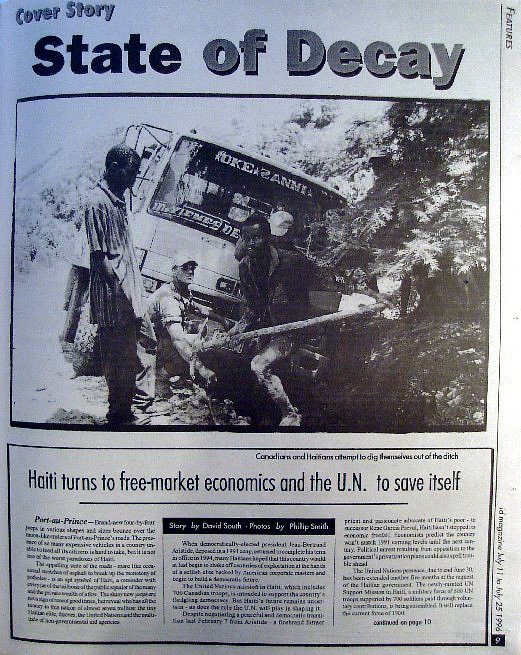

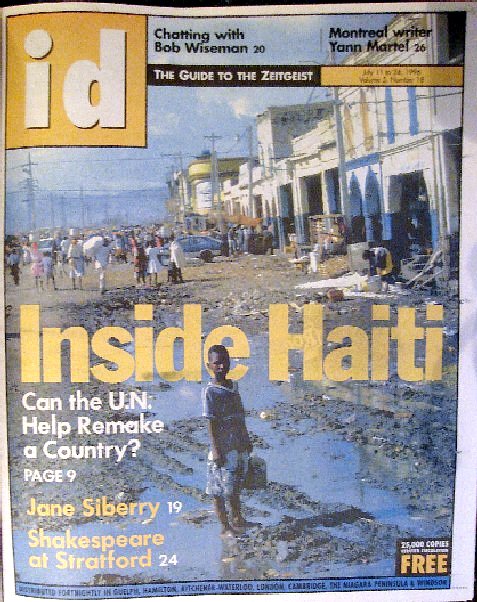

Port-au-Prince – Brand-new four-by-four jeeps in various shapes and sizes bounce over the moon-like craters of Port-au-Prince’s roads. The presence of so many expensive vehicles in a country unable to feed all its citizens is hard to take, but it is not one of the worst paradoxes of Haiti.

The appalling state of the roads – more like occassional stretches of asphalt to break up the monotony of potholes – is an apt symbol of Haiti, a reminder with every jar of the tailbone of the public squalor of the many and the private wealth of the few. The shiny new jeeps are not a sign of recent good times, but reveal who has all the money in this nation of almost seven million: the tiny Haitian elite, thieves, the United Nations and the multitude of non-governmental aid agencies.

When democratically-elected president Jean-Bertrand Artistide, deposed in a 1991 coup, returned to complete his term in office in 1994, many Haitians hoped that this country would at last begin to shake off centuries of exploitation at the hands of a selfish elite backed by American corporate masters and begin to build a democratic future.

The United Nations mission in Haiti, which includes 700 Canadian troops, is intended to support the country’s fledgling democracy. But Haiti’s future remains uncertain – as does the role the UN will play in shaping it.

Despite negotiating a peaceful and democratic transition last February 7 from Aristide – a firebrand former priest and passionate advocate of Haiti’s poor – to successor Rene Garcia Preval, Haiti hasn’t stopped its economic freefall. Economists predict the country won’t match 1991 earning levels until the next century. Political unrest resulting from opposition to the government’s privatization plans could also spell trouble ahead.

The United Nations presence, due to end June 30, has been extended another five months at the request of the Haitian government. The newly-minted UN Support Mission in Haiti, a military force of 600 UN troops supported by 700 soldiers paid through voluntary contributions, is being assembled. It will replace the current force of 1900.

Lousy loans

Meanwhile, the government of Rene Preval is negotiating with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the United States to get much-needed loans to help balance the budget. Critics say the world’s banks are trying to lock the poorest country in the Western hemisphere further into crippling debt. The Haitian budget is US $750 million, 60 per cent of which the government hopes to raise from loans.

But there is a condition. Haiti must embark on a structural adjustment programme: widespread firings of the public service, privatization of most of the public sector, loosening of controls over foreign capital, adherance to the ethos of global trading blocks espoused by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Some call this neo-liberalism, others neo-conservatism. Either way, it forces this impoverished country to limit how it can address rebuilding a crumbling infrastructure.

The government’s hands are tied, though, as the conditions were part of the deal to return Aristide to power.

A Canadian public relations company, Gervais-Gagnon-Covington Associates, has been paid US $800,000 by the American government to sell the idea of privatization of Haiti’s handful of idle and near-bankrupt state enterprises.

In order to plunge deep into this Haitian qaugmire, I pitch up at the legendary Hotel Olofsson -made famous by novelist Graham Greene in the Comedians – and begin interviewing in the languid atmosphere by the pool.

“Aristide has put Haitians in a giant trap with the IMF plan,” says Jane Regan, who runs an independent news service based in Port-au-Prince. “The US $1 billion in loans will double the national debt.

“Haiti used to be self-sufficient in rice – last year they bought US $56 billion in US rice. The roads are worse now than a year ago. Right now the UN mission is of questionable worth and Canadians are getting taken advantage of. They have been sent to clean up after the Americans. These are the same neo-liberal economic policies that hurt Canadian workers – just imagine what Haitians are feeling!”

Regan thinks that, so far, the only people to make any money out of this arrangement are businesses and the more than 800 NGOs operating in Haiti. And on that note, the feisty Regan disrobes and plunges into the Hotel’s pool.

According to Kim Ives, a reporter with the Haitian newspaper Haiti Progres, there are a few cracks in the solidarity between Preval and Aristide: “Aristide is hitting out against privatizations. In a two-hour TV interview, he drew a line between himself and Preval.”

One of the few visible signs of change in Haiti is the dusty Octobre 15 road leading from the airport past former president Aristide’s palatial home on its way to the wealthy suburb of Petionville. It is bordered on one side by Camp Maple Leaf, and on the other by dilapidated shanty towns and desperate street vendors.

Cynics point out the road conveniently serves the interests of the elite once again. It offers a direct and more or less pothole-free route from the secluded mansions of Petionville to the airport – a crucial escape route in a politically volatile developing country. In fact, a development of monster homes that would make a Canadian suburbanite blush is going up near the airport to capitalise on this.

Canadian troops

Caught between the Haitian government and its people is the United Nations, including Canada’s troops. Canadian troops form the first line of defence – along with Preval’s personal secuity guards – to defend the National Palace. They accompany the president wherever he goes, 24 hours a day.

Some fear growing resentment among Haitians for government policies will pitch the population against the soldiers.

At Camp Maple Leaf, the home base of Canada’s military contingent in Haiti, the troops are scrambling to adjust to a new mission sanctioned by the United Nations. As of June 30, they must take a back seat to the troubled Haitian police force as it tries to prove that the intensive training provided by police from around the world has paid off.

In the first week of July, the Canadian soldiers of the Royal 22nd Regiment – the famous Vandoos – receive confusing news about a change in their firing orders or Rules of Engagement. ROEs dictate the tone and behaviour of peacekeepers on a UN mission and, as the experience of Somalia demonstrates, they can be the difference between success and disaster.

As the new mandate starts, the Canadians are first told they will be only able to use deadly force to defend themselves and not Haitians. If a member of the government is assassinated, they must stand by. If a Haitian is clubbed to death before their eyes, they must stand back. It is a qualitative change from their ROEs prior to June 30.

Ottawa military spokesman Captain Conrad Bellehumour says the change is indicative of an evolving mandate. But a military spokesman in Haiti says the old ROEs are now back in force, and Canadians can intervene to save a Haitian’s life.

“Maybe somebody’s been listening to Jean-Luc Picard too much,” quips retired Brigadier-General Jim Hanson, in a reference to TV show Star Trek’s prime directive of non-interference in a culture.

Preval’s police

A large banner hangs over a Port-au-Prince street: “Police + Population = Securite + Paix”. The UN has placed its greatest emphasis on reforming Haiti’s policing and justice system. The Police Nationale d’Haiti (PNH) was formed, and the RCMP and the American Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) were asked to provide training. The idea is to break from the past – when the military used policing as an opportunity to terrorize the population – and establish a police force to serve and protect.

But the efforts of the Haitians and their international police advisers have had a mixed success. According to Canadian soldiers, the Haitian police need to be coaxed into conducting routine patrols and have not given up patrolling in large numbers in the back of a pick up truck with rifles at the ready. To be fair, seven police officers have been killed since January, in what many believe is an organized campaign of terror orchestrated by sympathizers of the old dictatorship and drug gangs.

According to Sergeant Serge Martin of the Vandoos, “The PNH use 15 police officers to patrol and don’t talk to anybody.”

“You don’t depend on police to protect you,” claims Regan. “The Haitian government has no control over them. You don’t know if there is going to be a coup tomorrow.”

Jean-Yves Urfie, editor of the pro-democracy Libete newspaper in Port-au-Prince, believes the campaign to kill police goes back to the United States. “I am convinced the coup d’etat was financed by the Republican administration. I believe the Republicans want to destroy things here to show (President) Clinton wasted his time bringing Aristide back.

“The government was forced to incorporate former members of the military into the police force. And it would be terrible if the population develops the impression all cops are bad.”

“They are 10 years away from a viable police force,” concludes Hanson.

A stop at the fourth precinct police station shows just how far things still need to go. At the counter is a lone police officer, sharply turned out in his beige shirt and yellow-striped navy pants, courtesy of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. But this proves to be a veneer of change. Canadian soldiers ask if everything is alright. They then ask to see tonight’s prisoners. The officer sheepishly leads the troops down a narrow corridor to 9 ‘ by 12 ‘ foot cell stuffed with nine prisoners. It is very hot and the stench from an open drain overflowing with sewage is nauseating.

Outside the Penitencier National in downtown Port-au-Prince, a yellow concrete structure with peeling pain, Haitians lined up to feed the inmates, talk about their frustrations with a justice system that has collapsed. Many complain that only the rich, who can hire lawyers, can enjoy the fruits of democracy. While state-directed beatings and killings have been dramatically reduced, most prisoners rot on remand until they are charged with a crime. Heiner Rosentdahl, the UN representative in Haiti in charge of prison reform, tries to be upbeat. “There have been no changes in conditions in Haiti’s prisons. Treatment of the prisoners is better, though there have been some abuses. We have developed a nation-wide register book of prisoners to help keep track of who is in prison.”

Another mixed blessing, according to Rosendahl, is the new requirement that all prisoners be fed two meal a day. The food is so poor, prisoners have been getting sick.

He is frustrated with the pace of penal reform. “The Haitian prison system hasn’t had a budget since October 1995, because of battles within the parliament,” he says. “The Haitian government didn’t ask for a plan to change this situation despite the minister of justice visiting the prison for the first time.”

According to Rosendahl, it is not the routine killing of thieves by mobs that worries the elite. Nor is it the assassination of police officers, or the untold thousands dying of disease and hunger. The only thing that is beginning to rock their world is a new phenomenon for Haiti: kidnapping and extortion.

Voodoo economics

For such a seriously depressed economy, there is an astonishingly large number of lottery booths – or Borlettes – on Haitian streets. They are so plentiful, they join gas stations as the main landmarks of the streets.

The industrial park which is now home to the remaining American troops stationed in Port-au-Prince, is a good monument to Haiti’s economic problems. Dilapidated and only barely functioning, this facility once supported, directly and indirectly, a large portion of the city’s population. As crummy as the sweatshop jobs were, they provided valuable income for the capital’s poor.

The Haitian economy under Francois Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude, before the chaos of the late 1980s and 1990s, was based on assembling manufactured goods for the US market. Haiti was the world’s largest producer of baseballs, and ranked as “top three in the assembly of such diverse products as stuffed toys, dolls and apparel, especially brassieres. All told, the impact of international subcontracting was considerable,” according to author Paul Farmer in his book, The Uses of Haiti.

Today, Pierre Joseph, a Haitian-American from New York City, has a new job: he screens the ID cards of Haitian workers as they enter the park. He says there were once over 50 factories operating here; now there are 30.

Evidence of Haiti’s economic collapse is everywhere. On the walls outside the National Palace is scrawled Aba Preval Granhanje – Preval is a liar. Across the wide boulevard in a square are around 75 homeless children. They joke with the Canadian soldiers, especially boyish 2nd Lt. Marc Verret, who looks like a baby in soldiers clothes. The kids beg him for water and money.

In the market area, the piles of garbage, rotting meat and excrement make a muddy devil’s stew. Homeless children sleep on top of the abandoned crates. One small child is curled up in an American flag, asleep.

Desecrating dead

The dead also suffer the indignities of economic ruin. Outside the gates of the Hopital Generale, a man lies dead on a broken trolley in the yard. Others still alive, with limbs missing, are sprawled out on the ground. Chickens and goats roam the grounds. In the back is the main morgue for Port-au-Prince. The odour just 25 feet from the entrance to the morgue is normal for this city strewn with rotting garbage and stewed by a hot sun.

Inside, an overpowering odour like rotten chicken meat is the product of 450 human cadavers. Like rag dolls laid out in a ghoulish toy store, row upon row of children dead from starvation and disease – Haiti’s infant mortality rate is 127 per 1,000 babies born – are stacked almost to the ceiling. There are also adults. Old women, young men badly mutilated for stealing, are strewn out on the dirty concrete floor and on shelves.

There is no refrigeration, and according to military doctor Major Tim Cook, “something really nasty is going to come out of there if they don’t do something.”

Proving peacekeeping

More is at stake in Haiti than the re-building of a politically and economically devastated nation. For Canada’s armed forces, shaken and little stirred by the Somalia scandal, it is an opportunity to make amends. This time around, the peacekeepers are keeping the needs of the local population foremost in their gun sights. When the Vandoos head out on another one of their 24-hour patrols, the atmosphere is friendly and filled with gentle ribbing with the locals. They have the advantage of being able to speak French, a language understood to varying degrees by most of the population.

The approach of the individual soldiers varies widely. On a routine patrol, Alpha Company engaged in good-natured kidding around, with splashing the locals the worst offence. But a day out with Charlie Company, led by Sergeant Serge Martin, proved another story. The two privates assigned to accompany a group of journalists were a couple of operators. The day included a visit to a perfume shop, a trip through the wharf area looking for prostitutes and constant propositioning of the local women.

One Canadian corporal with the Vandoos, Eric Charbonneau, has been trying to make a small difference to the lives of the 400 people living in the community of Cazeau, a shanty town near the international airport. He has started literacy and hygiene lessons and raised money to help the residents build concrete houses to replace the mud dwellings they currently inhabit.

“I was walking along the fence and started to build a relationship with the kids,” he explains. “Some guy approached me and needed some help. It took three weeks to build a relationship. They are too used to white people giving away things for doing nothing. They were surprised when they had to work for it.”

At the gates to Camp Maple Leaf is a spray-painted sign. In Creole, French and English beside a Canadian flag, it says “No More Jobs.” While it could look at home back in Canada, it illustrates how important the presence of soldiers, the United Nations and charities are right now to the economy.

Some observers see the UN presence as part of a slide back into dependency on foreign money, restricting Haiti’s ability to assert itself. But others believe the turn to the international community is Haiti’s last hope of breaking with a past littered with dictatorships and poverty.

According to Captain Roberto Blizzard – an erudite and wise observer of the situation – the base has been stampeded with desperate Haitians looking for work. Blizzard has tried to find work for as many Haitians as he can, even helping them to form a laundry co-operative he hopes will survive long past the Canadians’ stay.

“There is a danger of the Haitian people turning into full-time beggars,” he says with sadness.

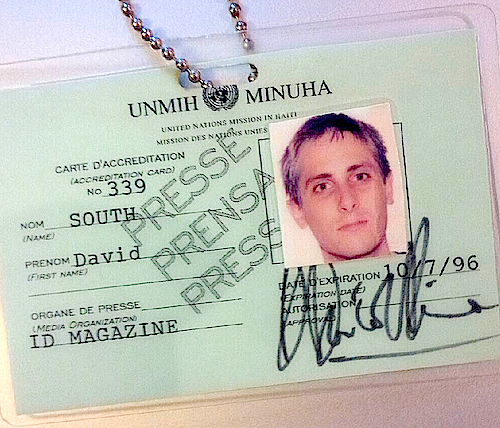

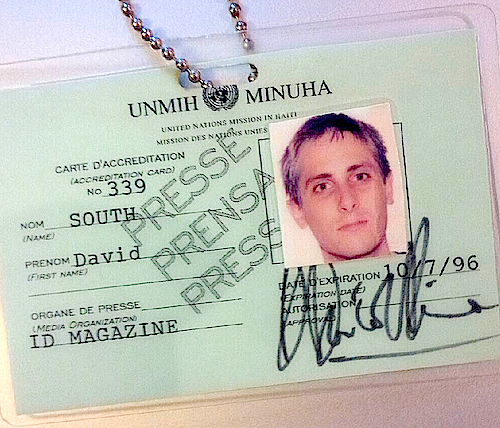

Id Magazine was published in Guelph, Ontario, Canada in the 1990s.

Id Magazine was published in Guelph, Ontario, Canada in the 1990s.  This story was researched and published in 1996.

This story was researched and published in 1996.

I covered the UNMIH mission in Haiti for Id Magazine in 1996.

I covered the UNMIH mission in Haiti for Id Magazine in 1996.

Opinion: Canada is allowing U.S. to dictate Haiti's renewal: More news and opinion on what the UN soldiers call the "Haitian Vacation"

By David South

Id Magazine (Canada), August 22 to September 4, 1996

An August 19 attack on the Port-au-Prince police headquarters by pissed-off former Haitian soldiers should be a wake up call to Canadians. So far, the Haiti UN mission has seemed as safe as the soldiers' quip, the "Haitian Vacation". The UN soldiers patrol the capital in rickety Italian trucks, stopping to chat with the locals. On the surface, this mission looks like summer camp compared to the nightmare of enforcing peace in the former Yugoslavia.

But for one crucial factor: The UN troops are propping up an increasingly unpopular government. A government that is seen by many Haitians to be getting its orders from Washington, not Port-au-Prince. Canadian troops lead the UN mission in Haiti and make up 700 of the 1500 soldiers stationed there (the rest are from Pakistan and Bangladesh). There is a serious danger they will be caught in the crossfire of any uprising or coup attempt.

Canadian troops shadow president Rene Preval 24 hours a day and also guard the National Police. When I visited the dilapidated palace in July, with its handful of Canadian troops banging away on laptop computers, I could only hope nobody will want to mess with the UN.

The two prongs of Haitian renewal - reforming the economy and the justice system - are both being directed by the U.S.. Haitian senator Jean-Robert Martinez had a theory about the August 19 attack, which killed a shoeshine boy. Martinez believes it was in retaliation for government plans to privatize Haiti's rotting nationalised industries - a condition for receiving loans from the U.S. and the Washington-based International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Haiti is a good example of the carnage of cynical U.S. foreign policy. The U.S. wooed and then coddled the corrupt Haitian elite to run its sweatshops. As the "development" organization USAID once said, Haiti could be the "Taiwan of the Caribbean". The U.S. trained the Haitian death squad Front pour l'Avancement et le Progres Haitien (FRAPH), who then littered the outskirts of Port-au-Prince with the bodies of former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide's supporters during the dark days of the 1991 coup.

Three weeks ago American troops from the 82nd Airborne plopped down on the streets of Port-au-Prince to spend a week patrolling. What kind of message does this send? This tells the Haitians that the UN isn't the real deal; that if they get out of line, the Americans will kick their butts. Why does Canada allow the U.S. to undermine the credibility of our peacekeeping mission?

More visits by the Americans can be expected. It is no accident that a medical team attached to the 82nd Airborne remains on duty at the American base in Port-au-Prince.

The so-called justice reforms are mostly window dressing. Canada spent $4,750,000 to build and renovate court houses for the same corrupt judges that were the problem in the first place. That's the equivalent of punishing a thief by buying him/her some new furniture.

Rather than telling the Haitians to tighten their buckles around hungry bellies, Canada should be leading the fight to pave roads and provide clean water and social services to all. Canada should not be helping to impose austerity economics on the Western hemisphere's poorest country.

David South is the Features Editor of id Magazine

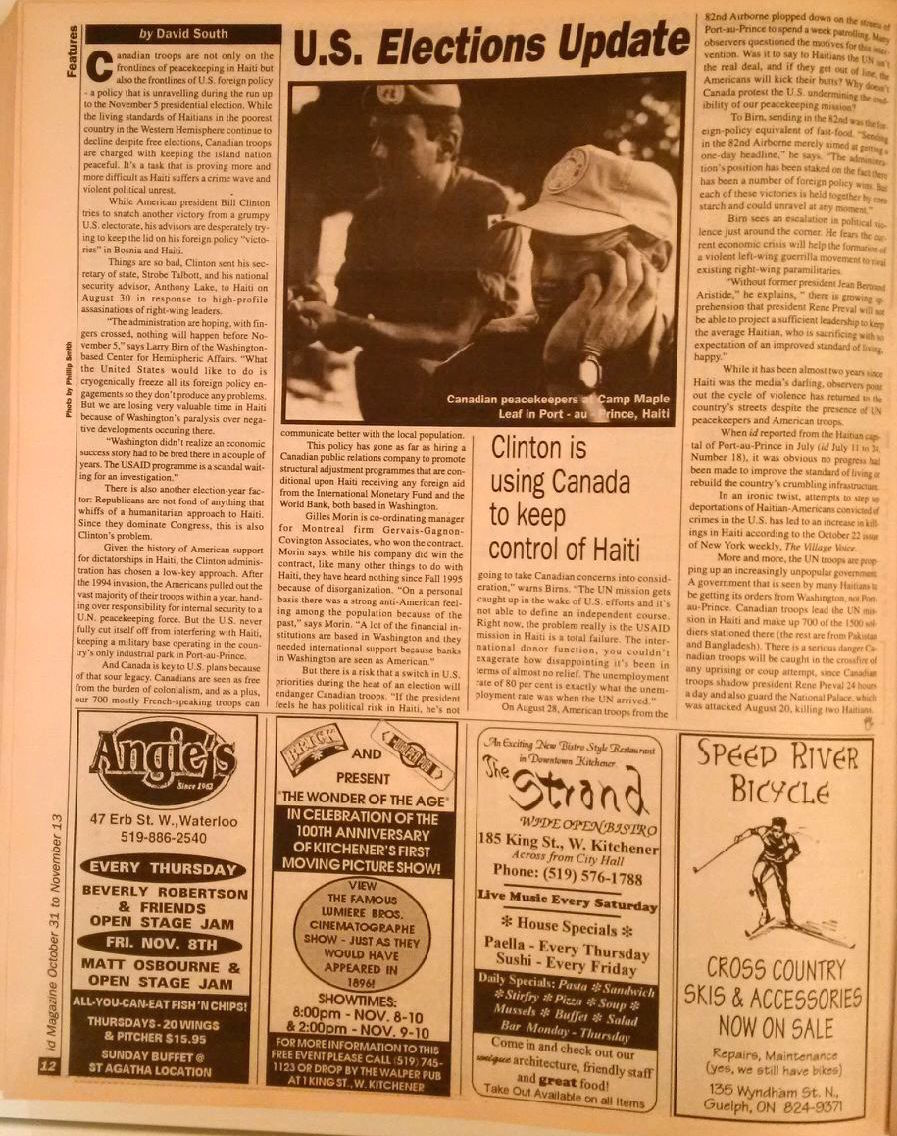

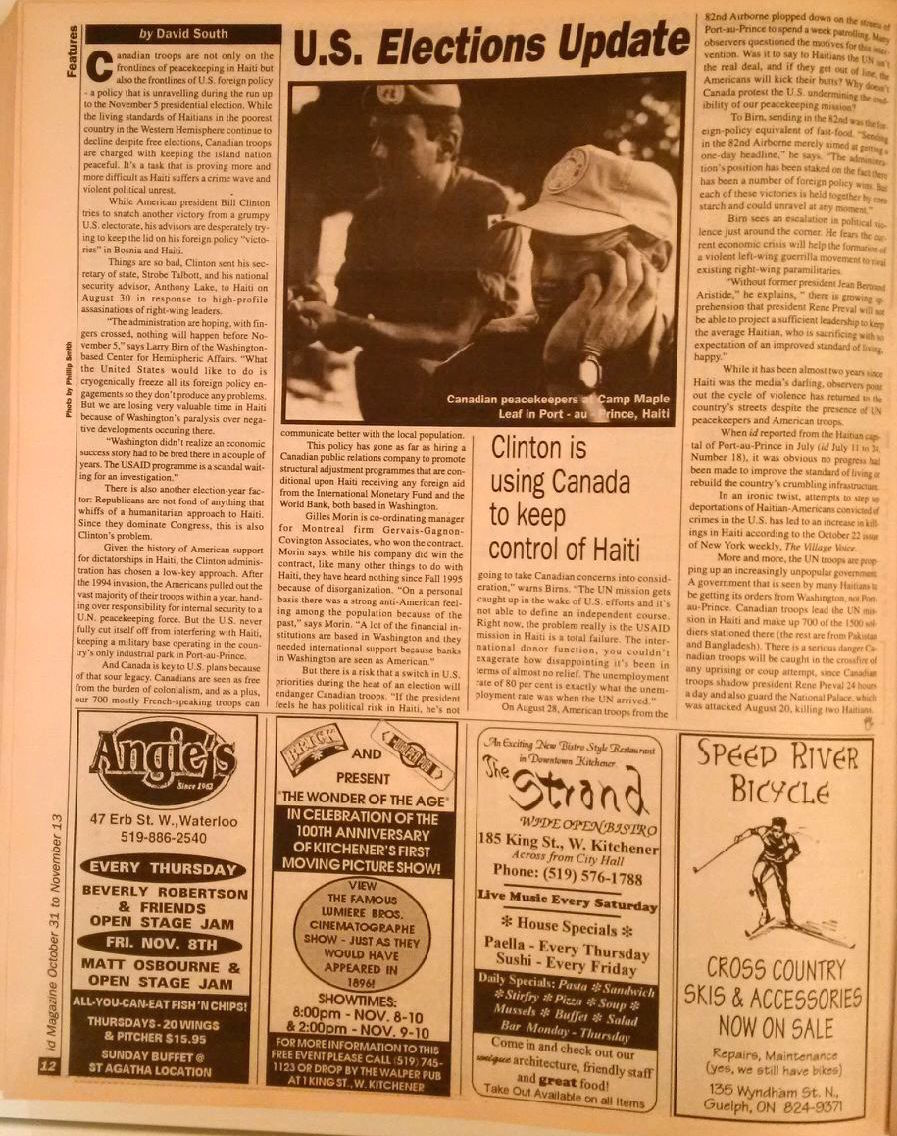

U.S. Elections Update: Clinton is using Canada to keep control of Haiti

By David South

Id Magazine (Canada), October 31 to November 13, 1996

Canadian troops are not only on the frontline of peacekeeping in Haiti but also the frontline of U.S. foreign policy - a policy that is unravelling during the run-up to the November 5 presidential election. While the living standards of Haitians in the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere continue to decline despite free elections, Canadian troops are charged with keeping the island nation peaceful. It’s a task that is proving more and more difficult as Haiti suffers a crime wave and violent political unrest.

While American president Bill Clinton tries to snatch another victory from a grumpy U.S. electorate, his advisors are desperately trying to keep the lid on his foreign policy “victories” in Bosnia and Haiti.

Things are so bad, Clinton sent his secretary of state, Strobe Talbott, and his national security advisor, Anthony Lake, to Haiti on August 30 in response to high-profile assassinations of right-wing leaders.

“The administration are hoping, with fingers crossed, nothing will happen before November 5,” says Larry Birns of the Washington-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs (COHA). “What the United States would like to do is cryogenically freeze all its foreign policy engagements so they don’t produce any problems. But we are losing very valuable time in Haiti because of Washington’s paralysis over negative developments occurring there.

“Washington didn’t realize an economic success story had to be bred there in a couple of years. The USAID programme is a scandal waiting for an investigation.”

There is also another election-year factor: Republicans are not fond of anything that whiffs of a humanitarian approach to Haiti. Since they dominate Congress, this is also Clinton’s problem.

Given the history of American support for dictatorships in Haiti, the Clinton administration has chosen a low-key approach. After the 1994 invasion, the Americans pulled out the vast majority of their troops within a year, handing over responsibility for internal security to a UN peacekeeping force. But the U.S. never fully cut itself off from interfering in Haiti, keeping a military base operating in the country’s only industrial park in Port-au-Prince.

And Canada is key to U.S. plans because of that sour legacy. Canadians are seen as free from the burden of colonialism, and as a plus, our 700 mostly French-speaking troops can communicate better with the local population.

This policy has gone as far as hiring a Canadian public relations company to promote structural adjustment programmes that are conditional upon Haiti receiving any foreign aid from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, both based in Washington.

Gilles Morin is co-ordinating manager for Montreal firm Gervais-Gagnon-Covington Associates, who won the contract. Morin says, while his company did win the contract, like many other things to do with Haiti, they have heard nothing since Fall 1995 because of disorganization.

“On a personal basis there was a strong anti-American feeling among the population because of the past,” says Morin. “A lot of the financial institutions are based in Washington and they needed international support because banks in Washington are seen as American.”

But there is a risk that a switch in U.S. priorities during the heat of an election will endanger Canadian troops.

“If the president feels he has political risk in Haiti, he’s not going to take Canadian concerns into consideration,” warns Birns. “The UN mission gets caught up in the wake of U.S. efforts and it’s not able to define an independent course. Right now, the problem really is the USAID mission in Haiti is a total failure. The international donor function, you couldn’t exaggerate how disappointing it’s been in terms of almost no relief. The unemployment rate of 80 per cent is exactly what the unemployment rate was when the UN arrived.”

On August 28, American troops from the 82nd Airborne plopped down on the streets of Port-au-Prince to spend a week patrolling. Many observers questioned the motives for this intervention. Was it to say to Haitians the UN isn’t the real deal, and if they get out of line, the Americans will kick their butts? Why doesn’t Canada protest the U.S. undermining the credibility of our peacekeeping mission?

To Birns, sending in the 82nd was the foreign-policy equivalent of fast-food. “Sending in the 82nd Airborne merely aimed at getting a one-day headline,” he says. “The administration’s position has been staked on the fact there has been a number of foreign policy wins. But each of these victories is held together by corn starch and could unravel at any moment.”

Birns sees an escalation in political violence just around the corner. He fears the current economic crisis will help the formation of a violent left-wing guerrilla movement to rival existing right-wing paramilitaries.

“Without former president Jean Bertrand Aristide,” he explains, “there is growing apprehension that president Rene Preval will not be able to project a sufficient leadership to keep the average Haitian, who is sacrificing with no expectation of an improved standard of living, happy.”

While it has been almost two years since Haiti was the media’s darling, observers point out the cycle of violence has returned to the country’s streets despite the presence of UN peacekeepers and American troops.

When id reported from the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince in July (id July 11 to 24, Number 18), it was obvious no progress had been made to improve the standard of living or rebuild the country’s crumbling infrastructure.

In an ironic twist, attempts to step up deportations of Haitian-Americans convicted of crimes in the U.S. has led to an increase in killings in Haiti according to the October 22 issue of New York weekly, The Village Voice.

More and more, the UN troops are propping up an increasingly unpopular government. A government that is seen by many Haitians to be getting its orders from Washington, not Port-au-Prince. Canadian troops lead the UN mission in Haiti and make up 700 of the 1500 soldiers stationed there (the rest are from Pakistan and Bangladesh).

There is a serious danger Canadian troops will be caught in the crossfire of any uprising or coup attempt, since Canadian troops shadow president Rene Preval 24 hours a day and also guard the National Palace, which was attacked August 20, killing two Haitians.

"U.S. Elections Update: Clinton is using Canada to keep control of Haiti": Id Magazine (Canada), October 31 to November 13, 1996

"U.S. Elections Update: Clinton is using Canada to keep control of Haiti": Id Magazine (Canada), October 31 to November 13, 1996

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:00PM

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:00PM  "Aid organization gives overseas hungry diet food": Now Magazine, December 1993.

"Aid organization gives overseas hungry diet food": Now Magazine, December 1993. 1993,

1993,  Americares,

Americares,  Canada,

Canada,  David South,

David South,  Georgia,

Georgia,  Now Magazine,

Now Magazine,  Slim-fast,

Slim-fast,  Toronto,

Toronto,  aid,

aid,  diet food,

diet food,  hungry,

hungry,  investigative journalism in

investigative journalism in  Canada,

Canada,  Magazine Stories 1990s,

Magazine Stories 1990s,  Media,

Media,  Now Magazine,

Now Magazine,  Toronto

Toronto