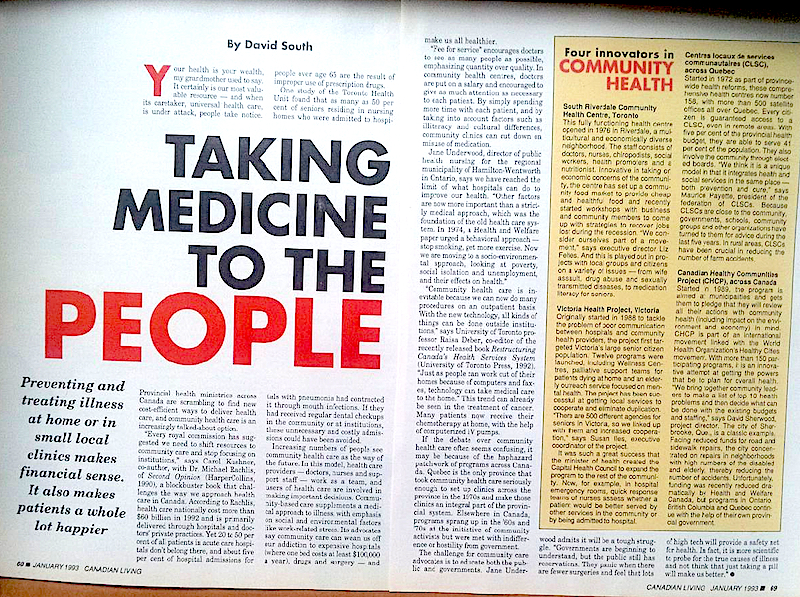

Taking Medicine to the People: Four Innovators in Community Health

Friday, June 12, 2015 at 2:48PM

Friday, June 12, 2015 at 2:48PM Preventing and treating illness at home or in small local clinics makes financial sense. It also makes patients a whole lot happier.

By David South

Canadian Living (Canada), January 1993

Your health is your wealth, my grandmother used to say. It certainly is our most valuable resource – and when its caretaker, universal health care, is under attack, people take notice

Provincial health ministries across Canada are scrambling to find new cost-efficient ways to deliver health care, and community health care is an increasingly talked-about option.

“Every royal commission has suggested we need to shift resources to community care and stop focusing on institutions,” says Carol Kushner, co-author, with Dr. Michael Rachlis, of Second Opinion (HarperCollins, 1990), a blockbuster book that challenges the way we approach health care in Canada. According to Rachlis, health care nationally cost more than $60 billion in 1992 and is primarily delivered through hospitals and doctors’ private practices. Yet 20 per cent of all patients in acute care hospitals don’t belong there, and about five per cent of hospital admissions for people over age 65 are the result of improper use of prescription drugs.

One study of the Toronto Health Unit found that as many as 50 per cent of seniors residing in nursing homes who were admitted to hospitals with pneumonia had contracted it through mouth infections. If they had received regular dental check-ups in the community or at institutions, these unnecessary and costly admissions could have been avoided.

Increasing numbers of people see community health care as the way of the future. In this model, health care providers – doctors, nurses and support staff – work as a team, and users of health care are involved in making important decisions. Community-based care supplements a medical approach to illness, with emphasis on social and environmental factors like work-related stress. Its advocates say community care can wean us off our addication to expensive hospitals (where one bed costs at least $100,000 a year), drugs and surgery – and make us all healthier.

“Fee for service” encourages doctors to see as many people as possible, emphasizing quantity over quality. In community health centres, doctors are put on a salary and encouraged to give as much attention as necessary to each patient. By simply spending more time with each patient, and by taking into account factors such as illiteracy and cultural differences, community clinics can cut down on misuse of medication.

Jane Underwood, director of public health nursing for the regional municipality of Hamilton-Wentworth in Ontario, says we have reached the limit of what hospitals can do to improve health. “Other factors are now more important than a strictly medical approach, which was the foundation of the old health care system. In 1974, a Health and Welfare paper urged a behavioral approach – stop smoking, get more exercise. Now we are moving to a socio-environmental approach, looking at poverty, social isolation, and unemployment, and their effects on health.”

“Community health care is inevitable because we can now do many procedures on an outpatient basis. With the new technology, all kinds of things can be done outside institutions,” says University of Toronto professor Raisa Deber, co-editor of the recently released book Restructuring Canada’s Health Services System (University of Toronto Press, 1992).

“Just as people can work out of their homes because of computers and faxes, technology can take medical care to the home.” This trend can already be seen in the treatment of cancer. Many patients now receive their chemotherapy at home, with the help of computerized IV pumps.”

If the debate over community health care often seems confusing, it may be because of the haphazard patchwork of programs across Canada. Quebec is the only province that took community health care seriously enough to set up clinics across the province in the 1970s and make those clinics an integral part of the provincial system. Elsewhere in Canada, programs sprang up in the ’60s and ’70s at the initiative of community activists but were met with indifference or hostility from government.

The challenge for community care advocates is to educate both the public and governments. Jane Underwood admits it will be a tough struggle. “Governments are beginning to understand, but the public still has reservations. They panic when there are fewer surgeries and feel that lots of high tech will provide a safety net for health. In fact, it is more scientific to probe for the true causes of illness and not think that just taking a pill will make us better.”

Four Innovators in Community Health

South Riverdale Community Health Centre, Toronto

This fully functioning health centre opened in 1976 in Riverdale, a multicultural and economically diverse neighborhood. The staff consists of doctors, nurses, chiropodists, social workers, health promoters and a nutritionist. Innovative in taking on economic concerns of the community, the centre has set up a community food market to provide cheap and healthful food and recently started workshops with business and community members to come up with strategies to recover jobs lost during the recession. "We consider ourselves part of a movement," says executive director Liz Feltes. And this is played out in projects with local groups and citizens on a variety of issues - from wife assault, drug abuse and sexually transmitted diseases, to medication literacy for seniors.

Victoria Health Project, Victoria

Originally started in 1988 to tackle the problem of poor communication between hospitals and community health providers, the project first targeted Victoria's large senior citizen population. Twelve programs were launched, including Wellness Centres, palliative support teams for patients dying at home and elderly outreach service focused on mental health. The project has been successful at getting local services to cooperate and eliminate duplication. "There are 500 different agencies for seniors in Victoria, so we linked up with them and increased cooperation," says Susan Lles, excutive coordinator of the project.

It was such a great success that the minister of health created the Capital Health Council to expand the program to the rest of the community. Now, for example, in hospital emergency rooms, quick response teams of nurses assess whether a patient would be better served by other services in the community or by being admitted to hospital.

Centres locaux de services communautaires (CLSC), across Quebec

Started in 1972 as part of province-wide health reforms, these comprehensive health centres now number 158, with more than 500 satellite offices all over Quebec. Every citizen is guaranteed access to a CLSC, even in remote areas. With five per cent of the provincial health budget, they are able to serve 41 pr cent of the population. They also involve the community through elected boards. "We think it is a unique model in that it integrates health and social services in the same place - both prevention and cure," says Maurice Payette, president of the federation of CLSCs. Because CLSCs are close to the community, governments, schools, community groups and other organizations have turned to them for advice during the last five years. In rural areas, CLSCs have been crucial in reducing the number of farm accidents.

Canadian Healthy Communities Project (CHCP), across Canada

Started in 1989, the program is aimed at municipalities and gets them to pledge that they will review all their actions with community health (including impact on the environment and economy) in mind. CHCP is part of an international movement linked with the World Health Organization's Healthy Cities movement. With more than 150 participating programs, it is an innovative attempt at getting the powers that be to plan for overall health. "We bring together community leaders to make a list of top 10 health problems and then decide what can be done with the existing budgets and staffing," says David Sherwood, project director. The city of Sherbrooke, Que., is a classic example. Facing reduced funds for road and sidewalk repairs, the city concentrated on repairs in neighborhoods with hig numbers of the disabled and elderly, thereby reducing the number of accidents. Unfortunately, funding was recently reduced dramatically by Health and Welfare Canada, but programs in Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec continue with the help of their own provincial government.

"Taking Medicine to the People" was published by Canadian Living in 1993.

"Taking Medicine to the People" was published by Canadian Living in 1993.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

1993,

1993,  By David South,

By David South,  Canada,

Canada,  Canadian Living Magazine,

Canadian Living Magazine,  HarperCollins,

HarperCollins,  Healthy Cities,

Healthy Cities,  University of Toronto,

University of Toronto,  University of Toronto Press,

University of Toronto Press,  WHO,

WHO,  four innovators in community health,

four innovators in community health,  small local clinics,

small local clinics,  taking medicine to the people in

taking medicine to the people in  Canada,

Canada,  Canadian Living,

Canadian Living,  Cities,

Cities,  Data,

Data,  Health,

Health,  University of Toronto

University of Toronto