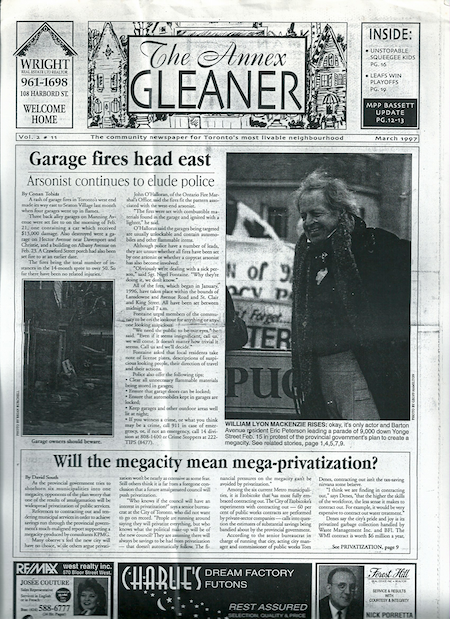

Will the megacity mean mega-privatization?

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:18PM

Saturday, June 13, 2015 at 1:18PM

By David South

Annex Gleaner (Toronto, Canada), March 1997

As the provincial government tries to shoehorn six municipalities into one megacity, opponents of the plan worry that one of the results of amalgamation will be widespread privatization of public services.

References to contracting out and tendering municipal services in order to achieve savings run through the provincial government’s much-maligned report supporting a megacity, produced by consultants KPMG.

Many observers feel the new city will have no choice, while others argue privatization won’t be nearly as extensive as some fear. Still others think it is far from a foregone conclusion that a future amalgamated council will push privatization.

“Who knows if the council will have an interest in privatization?” says a senior bureaucrat at the City of Toronto, who did not want to go on record. “People are running around saying they will privatize everything, but who knows what the political make-up will be of the new council? They are assuming there will always be savings to be had from privatization – that doesn’t automatically follow. The financial pressures on the megacity can’t be avoided by privatization.”

Among the six current Metro municipalities, it is Etobicoke that has most fully embraced contracting out. The City of Etobicoke’s experiments with contracting out – 60 per cent of public works contracts are performed by private-sector companies – calls into question the estimates of substantial savings being bandied about by the provincial government.

According to the senior bureaucrat in charge of running that city, acting city manager and commissioner of public works Tom Denes. contracting out isn’t the tax-saving nirvana some believe.

“I think we are finding in contracting out,” says Denes, “that the higher the skills of the workforce, the less sense it makes to contract out. For example, it would be very expensive to contract out water treatment.”

Denes says the city’s pride and joy is its privatized garbage collection handled by Waste Management Inc. and BFI. The WMI contract is worth $6 million a year, down from the $7.5 million a year it was costing to publicly run garbage collection. The price is fixed for five years, when it must be negotiated again. While the city made $1.9 million selling its old trucks, councillors set up a $4 million fund so Etobicoke could go back to collecting garbage itself if private companies tried to gouge the city.

Denes, who has been meeting with counterparts at other cities and the provincial government, believes the new Toronto will be divided up into several districts which private garbage collectors will have to compete for.

“Based on what I know, if you were to divide the city up into waste contracts, it would be at least four areas,” claims Denes. “No company can handle the whole city. You just can’t find a company that could handle a megacity. It would become a monopoly.”

Denes thinks the likely suspects for contracting out would be any manual labour work and the TTC. He thinks a megacity would be mistaken to contract out skilled work like surveying, arguing that skilled workers would use their desirability to their advantage and charge high consulting fees.

“The US cities have all gone through these exercises. They are in fact contracting services back in,” says Denes.

While the Tories have been slipperier than a scoop of ice cream about their specific privatization plans, one thing is clear: An essential element of the Tory economic vision is a greater role for the private sector in delivering public services. The $100,000 KPMG report plays to this, making it clear contracting out is a key means to saving money in the new megacity. The report claims between $28 million and $43 million per year could be saved from contracting out computer operations and some management; between $38.5 million and $68 million by contracting out fraud investigations; between $29.6 million and $54.5 million by contracting out road and electrical maintenance, snow removal and data collection; between $21 million and $39.4 million by contracting out garbage pick-up and processing.

The report also offers this proviso: “There is no such thing as automatic, cost-free savings from organizational change. The implementation process must be tightly managed to produce the savings suggested here.”

Ron Moreau is the administrator for Local 43 of the Metro Toronto Civic Employees Union, which represents over 3,000 public works workers and ambulance drivers at Metro.

“How will the megacity and municipalities cope with pressure from the public to hold the line on taxes? Where will councils find the difference between spending and revenues?” asks Moreau. “The level of service will suffer. When you contract out, public policy is held hostage by private enterpise.”

Moreau threatens that labour will play hardball with the new city. Most of the contracts for Moreau’s members run out on Dec. 31 of this year.

“Assuming the government doesn’t tamper with the labour legislation on our books, the unions can be organized into two large locals, one clerical/technical, the other outside workers. They would have effective bargaining clout.”

One major player looking for government contracts in a megacity will be Laidlaw Inc. While the company recently sold its garbage collection operations to an American firm, USA Waste, it still has interests in operating school buses and ambulances. Laidlaw is a heavy contributor to the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party, according to records kept by the Commission on Election Financing. Laidlaw has also made an influential new friend: in January, it hired former Metro chief administrative officer Bob Richards as its vice-president.

Ward 13 city councillor John Adams is definitely in the privatization-if-necessary-but-not-necessarily-privatization camp. “I don’t see everything being contracted out, but more stuff being put out for competitive bids.”

Adams thinks contracting out could be a good tactic to help modernize garbage collection, for example. He points to the City of Toronto’s deal with WMI to collect garbage at apartment buildings. In that deal, costs were reduced by $2.5 million over a five-year contract, and the crews on trucks were reduced from two to one. Instead of an extra crew member, closed-circuit television cameras were installed on trucks to speed up pick-up. Adams points out the crews are still unionized, but instead of CUPE it is the Teamsters.

“The way we pick up garbage from households is back-breakingly stupid. I think we need to rethink how we do it, to use machines more than people’s backs.”

But Adams doesn’t believe a megacity is a money-saver. “There will be a leveling up of wages. How long will two firefighters work side-by-side for different salaries? You can bet the union will negotiate an increase at the first opportunity.”

Adams thinks a megacity will be more prone to the slick lobbying efforts of companies like Laidlaw because councillors will be dependent on political parties to get elected. “The provincial government will contract out municipal government to Laidlaw,” he says sarcastically.

"Will the megacity mean mega-privatization?": March 1997.

"Will the megacity mean mega-privatization?": March 1997.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

Agenda 21,

Agenda 21,  Annex Gleaner,

Annex Gleaner,  By David South,

By David South,  Canada,

Canada,  John Adams,

John Adams,  March 1997,

March 1997,  Ontario,

Ontario,  Tories,

Tories,  Toronto,

Toronto,  government,

government,  megacity,

megacity,  privatisation in

privatisation in  Agenda 21,

Agenda 21,  Annex Gleaner,

Annex Gleaner,  Austerity,

Austerity,  Canada,

Canada,  Cities,

Cities,  Data,

Data,  David South Consulting,

David South Consulting,  Energy,

Energy,  Housing,

Housing,  Magazine Stories 1990s,

Magazine Stories 1990s,  NAFTA,

NAFTA,  Shock Therapy,

Shock Therapy,  Solutions,

Solutions,  Strategy,

Strategy,  Toronto,

Toronto,  Trade

Trade

Reader Comments