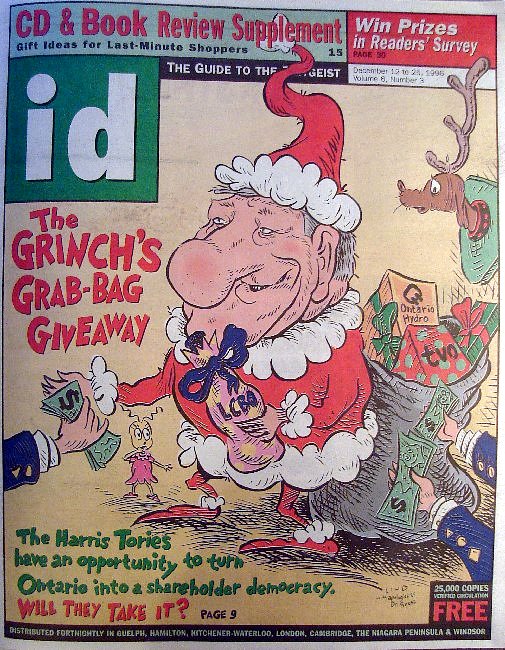

Province for Sale: Step Right Up For An Opportunity To Buy What You Already Paid For

Wednesday, February 22, 2017 at 7:54AM

Wednesday, February 22, 2017 at 7:54AM

“This is not being driven by fiscal or ideological motivation, though that may seem funny.” Conservative advisor James Small

By David South

Id Magazine (Canada), December 12 to December 26, 1996

It is looking more and more like the Conservative government will launch a massive privatization campaign by the middle of next year. And it is becoming clear how key government assets such as Ontario Hydro, liquor stores and public broadcaster TVO will end up in private hands. The prevailing ideology of key advisors to the Harris government, including influential financial heavyweights at Canada’s top underwriters, is leaning towards a free-for-all where the highest bidder will win.

To date, the government has been coy about its plans, occassionally making vague threats that certain services need to be “looked at.” Assets that could go on the block include road maintenance, jails and the Ontario Clean Water Agency. In August, the government appointed former banker Rob Sampson as the minister for privatization. His days as vice-president of corporate finance at Chase Manhattan make him a popular candidate with the suit, tie and blouse crowd on Toronto’s Bay Street.

While Sampson is so far surrounded by only a handful of advisors, the plan is to create a privatization agency that will supervise each sell-off after getting the go-ahead from Cabinet.

Sampson’s policy advisor James Small, sums up the government’s attitude: “This is not being driven by fiscal or ideological motivation, though that may seem funny. We can do better for less, even though that may sound trite.”

The government’s taxpayer-is-always-right attitude means it believes the best option is to float the newly privatized companies on the stock market, letting the highest bidder win.

“We have sophisticated investors in Ontario,” continues Small. “[Privatization] is not driving us to expand shareholders in Ontario. Can we, as taxpayers, benefit? What will give the best results. It is not ideological. In Canada we have a consumer culture and a very mature social structure. The market will determine what people will pay for things. We didn’t get elected to sell the family silver.

“There has been 16 years of this happening. But is Margaret Thatcher the way to go? One of the advantages for Ontarians is that we can pick and choose the best approach. It’s difficult to point to one part of the world, one way we could provide better service.”

Shareholder Democracy

A concept popularized by British prime minsiter Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, shareholder democracy actually saw the light of day in British Columbia back in 1979. Then, premier Bill Bennett embarked on an ambitious scheme to give every citizen of the province, including children, five shares in the British Columbia Resources Investment Corporation, a mining and logging company. Out of a population of 2.4 million, 2.07 million applied for the shares. While that idealistic experiment eventually failed as a series of bad deals pushed the share price down and arrogant executives pissed people off, it was a bold initiative.

Similar schemes have been used in Eastern Europe to increase private ownership in the economy.

But it is looking more and more like the government is going to try and avoid even a semblance of giving Ontarians a fair shake, by selling shares on the stock market to whoever can afford them. While the NDP and unions are opposed to privatization for some very good reasons, they are missing out on an opportunity to push the government to divide the shares up amongst all Ontarians (not necessarily a big stretch for the NDP, who brought us toll highways).

Shareholder democracy has developed two broad - and opposing - interpretations. For the left, a shareholder democracy in its truest sense is public ownership. For right-wing idealists, it means a nation of share owners playing the stock market with all the aggressiveness and greed of free-market capitalists.

Like any ideal, the reality is far more disappointing. Any small-time stock holder will tell you about arrogant CEOs and board members not listening to them. Ask any Ontarian on the street, and they will tell you about arrogant and incompetent civil servants who aren’t listening to them.

There is a more radical and fairer approach to privatization that would suit the populist rhetoric of the Conservatives. It involves selling shares along the lines of WWII war bonds. This solution would satisfy left-wing concerns the rich would run away with all the loot, while massively increasing share ownership in Ontario and raising funds to improve services and infrastructure. By selling millions of shares cheaply, and forbidding the trading of those shares, millions of Ontarians could reap the benefits of profit-making assets. This scheme would be contingent on reorganizing those agencies to become profitable, but could avoid a fire sale of taxpayer-funded agencies to wealthy corporations and investors. If critics of the government took the opportunity to guide the Conservatives, when a privatization is announced, towards mass share ownership, some good would come of it.

With all its scandals, bad publicity, grotesque executive salaries and inconsistent service that has turned privatization into a dirty word in the UK, the fact is share ownership did go up. In 1979 when Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher was elected, shares were owned by 2.5 million people; by 1992, 11 million people had shares or a quarter of the population. Narrowly defined, that is a success.

But the mainstream financial community loathes the idea for obvious reasons. At consultants KPMG, corporate evaluater John Kingston symbolizes the opposition to anything other than a straight sell-off at the stock exchange. “Issuance of shares to employees doesn’t put any new money into the coffers, like in the Eastern European example of gifting shares,” he says. “But selling shares to the public does provide some compensation. They must satisfy taxpayers by getting the right amount.”

“I think if government is going to privatize then it is a good time to do it,” says Deloitte and Touche’s Jim Horvath, a veteran of privatizations in Argentina, Hungary and Brazil, who supports a quick sell. “The stock market is up. There are a lot of deep pockets looking for investments.”

The mantra for an open sale will get louder as each privatization approaches. But such a sale does have its disadvantages.

Advantages of an open sale:

Can get the highest price. Use the funds to pay down debt or a one-time only increase in funds for something like health care. Argue protecting taxpayers’ interests by selling for the best price. The asset could raise funds on the stock market to improve infrastructure/services. Once in private hands, future governments will have a hard time trying to buy assets back.

Disadvantages of an open sale:

Taxpayers are also consumers; they could get screwed by any increase in rates. There is no guarantee the government will use funds for public good (maybe they will build another casino?). Any pay-off is once only, whereas the LCBO for example, makes money every year. Government could make a mistake and sell for too low a price.

Government Agenda

Two factors could significantly slow down the government’s ability to launch privatizations. The Conservatives have relished making cuts to government services despite labour unrest, but it has shown little skill at the more intellectual task of implementing a new philosophy. Major planks of their Common Sense Revolution, such as workfare, are bogged down and in chaos. Privatization will need a sophisticated sales job to counter-attack the slick television and newspaper ads unions have been running for the past year attacking privatization. Encouraging mass share ownership would show that leadership the government sorely needs.

The second liability is its own ambitious agenda. Already the Legislature has had to extend its term to try and deal with a backlog in reforms, including chopping another $3 billion, rearranging how government services are delivered and fighting the province’s doctors. But if it must privatize, then the honourable thing to do is to offer mass ownership. To do otherwise will show Ontario isn’t even capable of the heights of imagination some of Eastern Europe’s new democracies have shown.

Note: I debated this topic on CBC TV’s Face Off after this was published.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2021